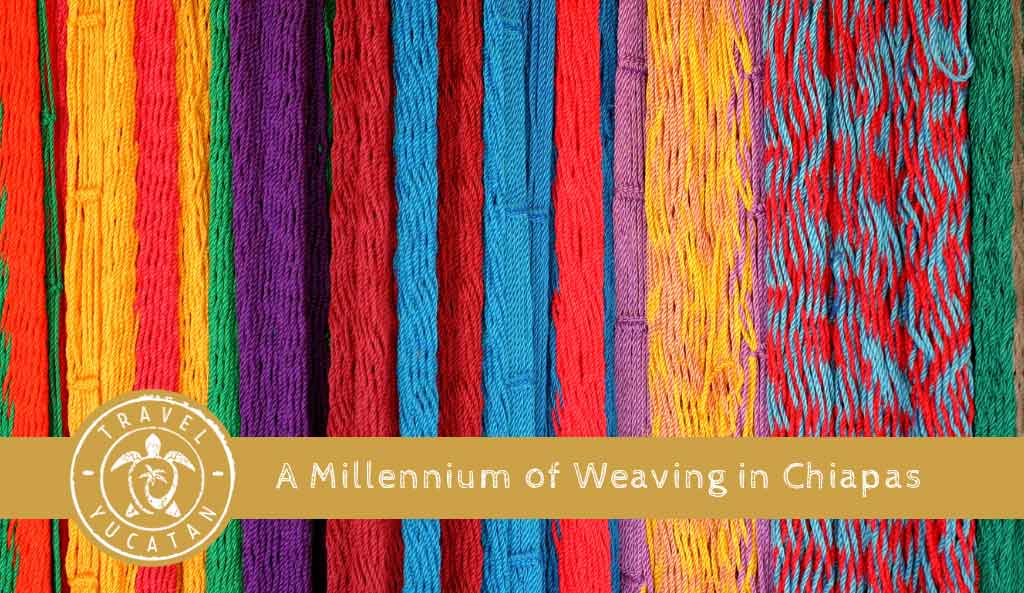

In the beginning of the world the Goddess of the Moon taught women to weave and to brocade sacred designs. Among the ruins of the Classic Maya, in painted murals, on painted vases, and in carved stone reliefs, rulers and priests are draped in eternal garments. They celebrate, and their ceremonial dress bears the message of that celebration.

In the rain forests and mountains of Guatemala and Mexico the Maya created a complex order which united literature, art, mathematics, astronomy, and calendrics. Obsessed with time, the Maya envisioned days and years moving in endless cycles of creations and destructions. They foresaw their own collapse – and renewal.

The Tzotzil and Tzeltal-speaking Maya, who inhabit the Highlands of Chiapas, Mexico, live in the shadow of a foreign culture. In 1524 Diego de Mazariegos conquered Chiapas, and under Spanish colonial rule the Maya suffered enslavement and the loss of their lands.

Throughout centuries of oppression the Maya have maintained their cultural integrity, a testament to the power and resilience of their traditions. Gods and heroes have been replaced by Catholic saints. Scarcity of land has forced most men to turn from farming to day labor. They still live within the rhythm of the seasons, however, planting corn and perpetuating the annual round of religious celebrations. Living between earth and sky, the Maya, like all rural peoples, depend upon the sun and rain and the fertility of the land. These and all plants and animal life are holy.

The tools and materials with which clothes are made are also holy, along with the designs that adorn them. The costume of each village strengthens communal solidarity and beliefs. Women of Chiapas weave, as they have since the beginning of time, as a sacred duty, and the designs they weave sustain the Maya world.

The hieroglyphic books have been destroyed. The great pyramids and palaces of stone have fallen into ruin. In the last thousand years weaving alone has given artistic expression to the profound wisdom of Maya culture.

In the textiles of Chiapas, the Maya concepts of time, space, and the mythological forces of nature are interwoven. Through repeated cycles of birth and decline, conquest and revival, weaving has preserved the design of the Maya universe.

Past and present in Maya culture are unified by symbols. The icons of the ancient Maya survive with similar meanings in the weavings of their descendants. The design of the universe (a diamond) that appears on a huipil from the Classic Maya site of Yaxchilan is also the dominant motif of modern huipils from San Andres Larrainzar. The toad, which appears on the robe of a woman of Yaxchilan, reappears in stylized form in contemporary weavings throughout the Highlands of Chiapas.

Textile designs have transcended time because they belong to the spirit. Designs are revealed in weavers’ dreams, rare ceremonial costumes are guarded by the elders, and the saints are dressed in layers of the finest “well-dreamt” huipils. Each saint’s array is a sacred repository. As the innermost huipil ages, fades, and turns to dust, a new huipil, faithful to the ancient tradition, is woven and offered to the saint.

In every period of cultural change there has been a rebirth of old designs, as well as innovations which have enriched the weaving art.

HOW TO LOOK AT MAYAN TEXTILES

Contemporary designs have four basic forms: diamonds, which symbolize the earth and sky as a unity; undulating forms, like snakes, which symbolize the fertile earth; forms with three vertical lines, which symbolize the foundation of the world, the community, and its history; and representational figures, such as toads (the musicians of the rain) and patron saints.

At the heart of the diamond is often a butterfly, symbol of the sun and centre of the Maya cosmos.

Diamond designs may cover the whole body of the huipil, they may be realigned to form a border or the diamond may be cut in half to form a horizontal design along the bottom of a brocade.

COLONIAL INFLUENCE

In 1524 the Spanish conquerors and their Aztec and Tlaxcaltec allies subdued Chiapas and soon afterwards established Cuidad Real (the Royal City) as the political, economic, and religious centre of the Highlands. Its first Catholic bishop, Bartolome de Las Casas, protected the Maya and converted them to Christianity.

The Spaniards were not the only inhabitants of the newly founded city. Mexicas and Tlaxcalans from Central Mexico, Mixtecas from Oaxaca, and Quiches from Guatemala were brought to settle in the Royal City. San Cristobal de Las Casas (the present name of this city) became a centre of cultural exchange between the Maya and the Indians from Mexico and Guatemala. Both pre-Columbian and European influences can still be seen in the costume and festivals of the Highlands.

The Indians of Central Mexico who settled in San Cristobal left permanent traces in the costumes of Zinacantan, Chamula, and other Maya communities. Characteristics of Aztec dress of the sixteenth century were knotted tassels on the bodice or a square design on the chest.

Although these styles have disappeared among the Aztecs, they made a lasting impression on the Maya of Chiapas. In fact, ancient Aztec fashions have served as models for the revival of costumes in the twentieth century.

Christian mortality of the colonial period imposed drastic changes in men’s costume. In their traditional loincloths and capes the Indians were practically naked. They turned their loincloths into sashes to tie on the short-legged pants designed for them by the Spanish, put on long-sleeved shirts, as required, and wrapped in new “ponchos,” resembled Spanish knights of the fifteenth century.

With the introduction of the foot loom at the end of the colonial period,, Aztecs living in the barrio of Mexicanos in San Cristobal began producing cloth for women’s skirts. The fabric was adopted by most Maya communities in the Highlands and is still being manufactured.

Wool, also introduced by the Spanish, replaced rabbit fur and quilted cotton as fabric for warm outer garments.

Silk, greatly prized by Spaniards, was grown in the New World and later imported in huge quantities from the Orient. The Maya were able to use silk for special garments, and these were the only native weavings the ruling class considered valuable.

“There is a great store of silk in the country (Zoque), in so much that the Indians make it their great commodity to employ their wives in working towels with all colors of silk, which the Spaniards buy, and send into Spain. It is rare to see what works those Indian women will make in silk, such as might serve for patterns and samplers to many school-mistresses in England” [description of Zoque textiles in 1627 by the English Dominican Friar Thomas Gage].

Spanish nuns of the colonial period taught Indian women cross-stitch embroidery and European patterns. Zoques living in the lowland town of Ocozocuautla still use those seventeenth-century designs. In the Highlands, Tzotzil women of El Bosque learned cross-stitch embroidery in about 1930, while the Tzeltal women of Chilon only recently began studying this technique at the nearby mission. Although Catholic nuns have been educating Indian women in European stitchery for over 400 years, interest in foreign designs has waxed and waned in different communities, at times dominating fashion, at other times being discarded for more traditional patterns.

Embroidered edgings that were popular in Europe in the eighteenth century decorate festival costumes of Chiapa de Corzo and blouses of Tzeltal and Tojolobal Maya.

Embroidery as a decorative technique existed long before the arrival of the Spaniards. The embroidered designs found on the huipils of Amatenango and the shawls of Chamula, for example, are not of European origin. Other Highland Maya communities have developed new styles of embroidery based on traditional designs.

In the nineteenth century a number of families from San Andres Larrainzar emigrated to the mild climate of Bochil. The women eventually replaced their heavy huipils with light cotton blouses embroidered to imitate brocading. This style of embroidery, at once innovative and traditional, has become increasingly popular throughout the Highlands.

RENAISSANCE

As the economic conditions have improved since the Mexican Revolution, designs and costumes have become more intricate and techniques more elaborate. Today, textiles have achieved the complexity of Classic Maya art. The inspiration for this creative revival has often come from dreams.

Once the Tzeltal women of Tenejapa did not know how to brocade. Santa Lucia, patroness of Tenejapa weavers, appeared to several women in dreams at the beginning of is century and asked them to make a brocaded huipil. In order to fulfill her wish, the women traveled to Tzotzil towns of San Andres Larrainzar and San Pedro Chenalho to study the art of brocading.

After mastering Tzotzil designs, they went on to create new motifs which now distinguish their community.

The inventiveness of the Tenejapan women inspired their teachers. Soon the women of San Pedro were setting new designs against the white spaces of their shawls.

In San Juan Chamula brocading died out at the end of the nineteenth century, yet several fine huipils of that period were carefully preserved as ritual costumes. Recently, at the request of the Chamulan elders, copies were made to adorn the saints, and forgotten designs have been reborn.

For the May today costume is memory. The designs preserve their vision of the world, their identity, and their relationship with nature.

The propitiation of time was also fundamental to their ancestors, whose durable monuments of stone conserve the most fragile of arts, textiles.